Last month, after immersing myself in Brooklyn’s artisanal-food scene, I felt the need that many in my home borough have these days: to get out on a farm and smell the manure. So I drove an hour and a half southwest of New York City to spend the day with three generations of dairy farmers.

Bob Fulper, 85, was born on what is now Fulper Farms in West Amwell Township, N.J. So was his son, Robert, 54, who currently runs the place with the help of his brother, Fred, who is 51. Robert’s daughter, Breanna, 24, recently graduated from Cornell with a degree in dairy management. Breanna would like to lead the family business into the next generation, but she realizes it might not be financially possible. The modern dairy farm, it turns out, represents many of the volatile and confusing trends that have roiled the U.S. economy over the last decade.

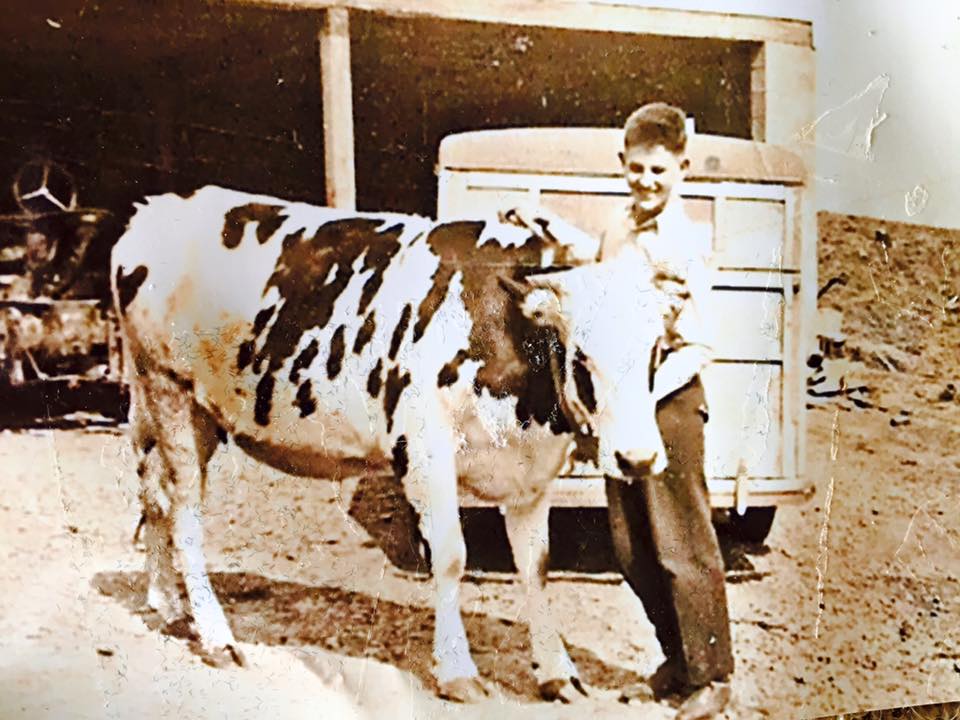

This, despite the fact that dairy farming has become shockingly more productive. When Bob was a kid, during the Depression, he and his 10 siblings milked the family’s 15 cows by hand and produced 350 pounds’ worth of milk per day. By the time Robert was a teenager, in the 1970s, the farm had grown to 90 cows — all of which were milked automatically through vacuum technology — and sold around 4,000 pounds of milk per day. Now the Fulpers own 135 cows, which produce more than 8,000 pounds of milk.

So the farm should be more lucrative, right? Robert showed me exactly how much money he and his brother made last year, an unusually profitable one for the dairy industry. He asked me not to reveal the number, but let’s put it this way: Robert and Fred start work at 4:30 a.m., finish at 7 p.m. and trade Sundays off. If you divide their 2011 profit by their weekly hours, they earn considerably less than minimum wage. Unlike in their father’s day, they have little money left over to invest in new equipment. One of their computers runs on MS-DOS.

How could Robert and Fred — who produce so much more milk than their dad — end up making less money? There are a number of reasons, some obvious, others less so. Milk went from a local industry to a national one, and then it became international. The technological advances that made the Fulpers more productive also helped every other dairy farm too, which led to ever more intense competition. But perhaps most of all, in the last decade, dairy products and cow feed became globally traded commodities. Consequently, modern farmers have effectively been forced to become fast-paced financial derivatives traders.

This has prompted a significant and drastic change. For most of the 20th century, dairy farming was a pretty stable business. Cows provide milk throughout the year, so farmers didn’t worry too much about big seasonal swings. Also, at base, dairy-farming economics are simple: when the cost of corn and soybeans (which feed the cows) are low and milk prices are high, dairy farmers can make a comfortable living. And for decades, the U.S. government enforced stable prices for feed and for milk, which meant steady, predictable income, shaken only by disease or bad weather. “You could project your income within 5 to 10 percent without trying too hard,” says Alan Zepp, a dairy-farm risk manager in Pennsylvania.

But by the early aughts, to accommodate global trade rules and diminishing political support for agricultural subsidies, the government allowed milk prices to follow market demand. People in other parts of the world — notably China and India — also became richer and began demanding more meat and dairy products. Animal feed, especially corn and soybeans, became globally traded commodities with all the impossible-to-predict price swings of oil or copper. Today Robert can predict his profit or loss next month with all the certainty that you or I can predict the stock market or gas prices. During my visit, Robert said that his success this year will be determined by, among other things, China’s unpredictable economic growth, the price of gas (influenced, of course, by events in Iran and Syria) and the weather in New Zealand (a major milk exporter), where a drought can send prices skyrocketing.

There are ways to manage, and even profit from, these new risks. The markets offer a stunning range of complex agricultural financial products. Dairy farmers (or, for that matter, anybody) can buy and sell milk and animal-feed futures, which allow them to lock in favorable prices, hedge against bad news in the future and so forth. There’s also a new product that combines feed and milk futures into one financial package, allowing farmers to guarantee a minimum margin no matter what happens to commodity markets down the road.

The Fulpers, like most people, are too busy with their day jobs to truly monitor the markets. But dairy farming has its own 1 percent: that tiny sliver of massive farms, with thousands of cows, that make the biggest profits and are better equipped to pay agriculture-futures experts to help them manage risk. They continue to invest and grow. Unable to keep up with the changes, many smaller farms have gone out of business in the past decade.

Robert Fulper says that he and his brother have done a good job keeping their farm alive and healthy during this chaotic time, just as their father transformed the tiny, Depression-era farm into a solid, modern business. Now “the next generation is going to have to figure some things out,” Robert says, looking at his daughter, Breanna. The good news is that she’s already trying. While at Cornell, Breanna used her family farm as a case study and developed a business plan to profit from their proximity to New York City and northeastern New Jersey. She began a summer camp in which kids spend a week caring for cows, learning about agriculture and running around a huge open space for $425 per week. Now the camp is almost as profitable as a year of milking cows. “That summer-camp program put me through Cornell,” Breanna says with a laugh. She’s also negotiating with a cheesemaker to turn their milk into high-value Fulper-branded cheese.

Bob, her grandfather, told me a number of hysterical, unprintable farm jokes during my visit, but he turned pensive when it came to his farm’s future. When times were bleak, he said, it used to be possible to work your way out of the problem. “You just stay in the cowshed longer, work harder,” he says. Now, he realizes, “if you don’t use your head, your hands aren’t gonna help you.” And even then, you might not make it.

Originally published by Adam Davidson for The New York Times Magazine